On the Senate Floor, Collins, Shaheen Urge Action on Bipartisan INSULIN Act to Lower Surging Costs of Lifesaving Drug

“The INSULIN Act of 2023 would address the fundamental issues facing the insulin market. For children, teens, and adults, with type 1 diabetes, insulin is not optional. It is literally a matter of life and death.”

Click HERE to watch Senator Collins’ remarks.

Washington, D.C. – U.S. Senators Susan Collins (R-ME) and Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH), co-chairs of the Senate Diabetes Caucus, delivered remarks on the Senate floor today to advocate for their bipartisan bill, the Improving Needed Safeguards for Users of Lifesaving Insulin Now (INSULIN) Act of 2023. This legislation would comprehensively address the high costs of insulin, removing barriers to care and making it more accessible for millions more Americans.

More than 37 million Americans have diabetes, and an estimated 88 million more may be at risk of developing the disease. Diabetes is one of the leading causes of death in the United States, claiming over 100,000 lives in 2021. It is also one of the most expensive chronic conditions in the nation, costing Americans a combined total of $327 billion per year and creating a serious financial burden for many Americans who rely on it to survive. According to the Health Care Cost Institute, nearly 9 percent of patients with private insurance paid an average of $403 per month for their insulin in 2019.

The INSULIN Act would directly address the root problems in the insulin market causing high list prices, while simultaneously extending vital patient protections, fostering competition, and broadening access to needed insulin products.

As the founder and co-chair of the Senate Diabetes Caucus, Senator Collins has long worked to increase awareness of the threats posed by diabetes, invest in research, and improve access to treatment options.

Senator Collins’ full remarks can be found HERE or below:

Thank you, Mr. President. Mr. President, I'm pleased to rise this evening with my colleague and dear friend, Senator Jeanne Shaheen, to discuss the compelling need to lower the cost of insulin for Americans with diabetes, by reforming the system for getting the drug from the manufacturer to the consumer, and by capping the out-of-pocket price. I want to commend Senator Shaheen, for her long-standing devotion and hard work on this issue. For her, this is both a matter of policy and personal, as she has described, and I could have no better co-chair, of the Senate Diabetes Caucus, than my colleague from New Hampshire. We are focused on policies that will improve the lives of those who are living with diabetes. Building on our past efforts, we've introduced a new bill, the Improving Needed Safeguards for Users of Lifesaving Insulin Now, or the INSULIN Act of 2023.

Mr. President, a little background may be useful. As my colleague from New Hampshire has mentioned, when a team of three scientists, at the University of Toronto, first isolated insulin in 1921, they sold the patent for $1 each to the university, an act intended to ensure that those in need of insulin would always have an affordable access. They explicitly stated that profit was not their goal, nor their motive. And yet, in recent years, the cost of insulin has soared, and insulin costs have become unaffordable for far too many individuals with diabetes. Between 2007 and 2018, the average list price of insulin increased by 262 percent. In 2019, nearly 9 percent of patients with private insurance paid on average $403 per month for their insulin. This shows the huge increase in the list price, between 2012 and 2021. This is the net price. I'll explain that in a moment. Tens of millions of Americans rely on insulin as part of their daily treatment.

For children, teens and adults, with type 1 diabetes, insulin is not optional. It is literally a matter of life and death. About 20 percent of those with type 2 diabetes rely on insulin. Mr. President, I have heard far too many stories, from people in my state and from across the country, who, because of the escalating costs, have had to ration their insulin, an extremely dangerous practice. These drastic measures can result in major risks that can compromise their health, and even jeopardize their lives. Let me share one such story. Recently, I met with Bek Hoskins, of Chelsea, Maine, through her advocacy with JDRF. Bek was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes said age 10. When we discussed insulin affordability, Bek shared her "insulin story." As a young adult, shortly after she was no longer covered by her parent's insurance, Bek was forced to ration her insulin, to make it last longer, because she simply could not afford the exorbitant price. In one profoundly memorable instance, Bek pushed her body's limit too far. Her husband, Barrett, rushed her through a snowstorm to an emergency room, as she was in excruciating pain. Bek nearly died, because she tried to go without her lifesaving, fast-acting insulin for two days.

Mr. President, the situation that Bek faced, sadly, is not an isolated example. We simply must address this problem. Senator Shaheen and I have long led action in the Senate to improve the lives of those living with diabetes and to reduce insulin prices. We spearheaded the bipartisan INSULIN Act, last Congress, to comprehensively reform the system that determines the cost of this lifesaving drug. And I'm pleased that the market has been responding to our efforts. The recent decisions, by the three major manufacturers of insulin, to cut list prices, is certainly encouraging. But there is more work to be done. We need legislation to reform the fundamental factors that distort the insulin market, including, a purchasing system that is rife with perverse incentives, conflicts of interest, and very limited biosimilar competition. And we've introduced legislation to do just that. It would guarantee out-of-pocket limits, for patients with commercial insurance, encourage biosimilar development to lower list prices through competition, and reform the practices of pharmacy benefit managers. That would improve the insulin market, giving patients long-term benefits.

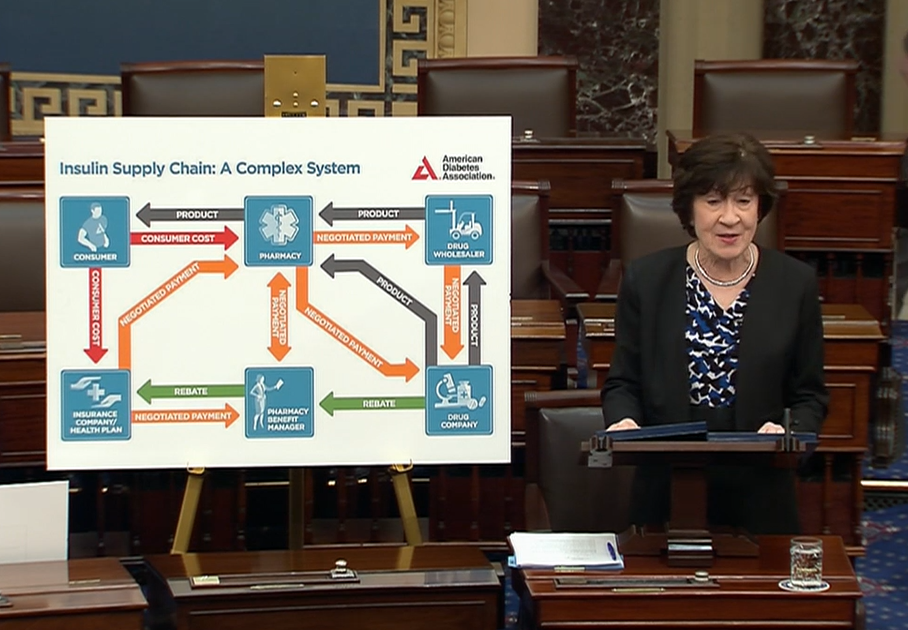

First, our bill would limit cost sharing to no more than $35, or 25 percent of the list price, per month, starting in 2024, for at least one insulin in each type, or dosage form. Under our bill, insurers and pharmacy benefit managers, known as PBMs, would be prohibited from placing utilization obstacles, such as prior authorizations or step therapy, on products with capped costs. These important protections deliver immediate out-of-pocket relief. Second, our bill would tackle the perverse incentives that encourage the high list prices. Many people wonder why price variations of a product that's been available for more than 100 years has increased dramatically. And the answer is that the market is rife with conflicts of interest, and lacks transparency. What happens is the PBMs negotiate discounts from the list price to the net price of insulin. Well, what happens to the money that's in between? There's an incentive for the pharmacy benefit manager to select the high-cost insulin, because they are paid based on a percentage of the cost, in many cases. So, that's what you see here. So, a lot of the benefit of this lower net price that's been negotiated, does not reach the consumer.

In 2018, as Chair of the Senate Aging Committee, I held a hearing that examined the role of PBMs and rebates in the insulin supply chain, and their effect on increasing insulin prices. At the hearing, an American Diabetes Association expert displayed this chart, that I am showing on the Senate floor, which is called, Insulin Supply Chain: A Complex System. I think that understates the situation. This is so convoluted and lacks transparency, that no wonder we end up with a system that is rife with conflicts of interest. One thing is clear, the way that the rebate functions, in the current market, is the key factor, not in lowering the cost to the consumer, but in driving up insulin costs. The way the rebate system works, encourages PBMs to select a higher price insulin, for an insurer's formulary. PBMs often choose the highest-cost insulin, because, as I mentioned, their compensation, in the form of sharing part of the rebates, is based, frequently, on a percentage of the list price. Now, let me now give you one case study that involves biosimilars. Biosimilar products are generic forms of biologics, like insulin, and like generics, they're lower cost. But the PBM incentive structure can be stacked against them.

For example, Sanofi manufactures a popular insulin product called Lantus. In 2021, Viatris launched two identical versions of its interchangeable biosimilar for Lantus. One was a branded, interchangeable product with a high list price. The second was an unbranded, interchangeable biosimilar with a low list price. The higher-priced version, of the exact same insulin interchangeable drug, was selected for formularies, that are run by the insurers, while the lower-priced one was not. Think about that, Mr. President. This proves the perverse incentives in the system. No major formulary preferred the lower list-price version, even though it is the exact same product and costs less. That's how this system operates. Rebaiting practices have slowed biosimilar adoption, and lower priced products are still struggling to compete. To date, no major formulary prefers the lower list-price versions of the branded products. Insulin rebates average between 30 and 50 percent, and can reach as high as 70 percent, for the most commonly used insulin products, significantly higher than the average rebate for other types of drugs.

Our INSULIN Act addresses the current distortions in the market that decrease affordability for patients, by requiring PBMs to pass through 100 percent of the insulin rebates. By removing the PBM's share of the rebate, the INSULIN Act would eliminate the incentive for PBMs to choose the higher list-price product. Finally, our bill takes a number of steps to promote biosimilar competition. More choices in the insulin market would drive down prices, by creating competition. The INSULIN Act would create a new, expedited FDA pathway to promote biosimilar competition. This provision is modeled after a successful law, I authored with former Senator Claire McCaskill, in 2017, to improve competition for generic drugs. And according to the FDA, nearly 200 products have benefited from the process we created. So, let's extend that to biosimilars, as the Shaheen-Collins Bill would do.

The INSULIN Act would take similar steps to enhance that regulatory certainty for biosimilar drug companies. You know, it's ironic that there's a biosimilar insulin available in Canada and Europe right now, that cannot be produced for US distribution, because the FDA has taken nearly 10 months to reinspect the safety of the facility where the drug is being manufactured. So, what we want to do is expedite the regulatory process. Mr. President, we know regulatory barriers are not the only challenge for biosimilars. The incentives in the current insulin market, for PBMs, often prohibit biosimilars from securing fair formulary placement, as indicated by the example I described earlier. So, one other step that our bill would take to ease some of the access challenges for biosimilar drugs, is to provide CMS with the authority to approve mid-year, Medicare Part D formulary changes, when a biosimilar enters the market.

Mr. President, The INSULIN Act of 2023 would address the fundamental issues facing the insulin market. Expensive, convoluted, opaque rebates pocketed by the PBMs; a lack of biosimilar competition and patient affordability. Like Senator Shaheen, I am so pleased that our bill has been endorsed by the American Diabetes Association, JDRF and The Endocrine Society, and I thank them for their support of this bipartisan legislation. I encourage our colleagues to join us in supporting these much-needed reforms. Thank you, Mr. President.

###